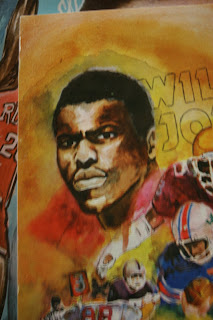

Jesse Owens

Jesse Owens Oscar Charleston

Oscar Charleston

The recent public appearance by Evander Holyfield at a D.A.R.E. graduation at Southwest Laurens Elementary brings to mind a day, nearly sixty years ago. On that day two of the greatest athletes in the history of the world displayed their talents for thousands of admiring fans, who for the first time got to see their heroes up close and in person. One man was one of the greatest track and field athletes of all time. The other man, whose career was thwarted by baseball commissioner Kennesaw Landis’s refusal to allow black athletes in major league baseball, was one of the greatest players in the history of the Negro Leagues.

The friends of Washington Street School were raising money for athletic programs at the school. On April 10, 1940, a special benefit was planned at the fairgrounds on Telfair Street. The fairgrounds had seen great athletes and spectacles before. In 1918, the New York Yankees defeated the Boston Braves on the fairground diamond. The St. Louis Cardinals stopped in town on their way back to St. Louis after spring training to play a game against the Oglethorpe University Petrels in 1933. Two years later, the Cardinals returned to play the University of Georgia Bulldogs. In all, eight members of the Baseball Hall of Fame, Miller Huggins, Frank “Home Run” Baker, Dizzy Dean, Rogers Hornsby, Leo Durocher, Frankie Frisch, Joe Medwick, and Jesse Haines played on the sandy field located at the northwest corner of Telfair and Troup Streets. County fairs, circuses, and even a performance by cowboy legend Tom Mix had drawn thousands to the old 12th District fairgrounds.

The feature attraction of the day was billed as "the world's fastest human." His name ranks among the greatest athletes in Olympic history. In the 1935 Big Ten Track and Field Championships, he broke five world records and tied one in a forty-five minute period. In the 1936 Summer Olympics, he won four gold medals. At the time he held the world record for a long jump, 220-yard hurdles, and 220-yard dash. He has tied the world record for the 100-yard dash. He also had tied the world record with a time of 10.3 seconds in the 100-meter dash. A 20.7 second time in the 200-meter dash gave him another Olympic record. He was put on the 400-meter relay team at the last minute. The team set a world and Olympic record.

Interestingly, it was one of the German competitors who gave him a helpful hint which allowed him to beat the German in the long jump. The German jumper told the American track star to make a mark a few inches short of the foul line and to jump from that point. It worked. He set an Olympic record that stood for twenty-five years. He won the Gold medal - and the German, won the Silver. He stated that all of the medals he won wouldn’t replace the friendship he had developed with Lutz Long, the German athlete. Long was killed in the Battle of St. Pietro on July 14, 1943. Adolph Hitler was so enraged that he stormed out of the stadium refusing to present the medals.

The world champion American athlete’s name was, of course, Jesse Owens. In Dublin, Owens was scheduled to compete in a dash around the baseball diamond, a one hundred yard dash against a race horse, a running broad jump, and a one hundred twenty-yard low hurdle race. After his exhibition, Owens gave an interview over a loud speaker answering questions from his fans. Owens never enjoyed the attention that should have been given to him. In the mid 1930s, he was ignored when national amateur athletic awards were handed out. He later fell from grace with some who disagreed with his comments and beliefs on social relationships in America.

Preceding Owens' feats of human speed that day, there was an exhibition baseball game between the Toledo Crawfords and the Ethiopian Clowns. Jesse Owens was the business manager of the Crawfords. The game was played before fans, both white and black. The two teams traveled the country stopping nearly every day to play a baseball game - some times before a few hundred fans and other times, before tens of thousands.

The Crawfords began playing on a sand lot in Pittsburgh in the 1920s. In those early days, legendary catcher Josh Gibson was on the team. Their owner, Gus Greenlee, used the profits from his gambling and liquor activities to buy the best players in the Negro Leagues. Greenlee built and equipped a lighted stadium, years before the Major Leagues began playing at night. The Crawfords joined the re-organized Negro National League in 1933. It was the first year of the Negro League All Star Game - the East-West Classic, which was created by Greenlee. The Crawfords won the National League championship in 1935. In 1937, their star players, led by Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson, left the team in a salary dispute. The team was never the same. Greenlee sold the Crawfords, and the team moved to Toledo, Ohio. One star remained with the team. His name was Oscar Charleston, known by the press writers as “The Hoosier Comet.”

The Crawfords were led by Oscar Charleston, who was playing in his last season for the team. Charleston was a slick fielder with a lifetime average of .380. Many regard him as the greatest Negro League player of all time. John McGraw called him “the greatest player ever.” In 1921, he batted .446 with 14 home runs for the St. Louis Giants. In one nine-year span, Charleston batted over .350 in all nine seasons, twice hitting over .400. Charleston joined the Crawfords in 1932 and consistently hit around .350. Charleston was a fan and player favorite. As a fielder, he was known as “The Black Tris Speaker”; as a runner, he was known as “The Black Ty Cobb;” and as a power hitter, he was known as “The Black Babe Ruth.” Oscar Charleston, who ended his career with a .376 batting average, was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1976.

The Ethiopian Clowns were a true barnstorming team. They were the clown princes of Negro League Baseball, comparable to the Harlem Globetrotters’ basketball team. While they had no great stars, the Clowns, who eventually moved to Indianapolis along with the Crawfords, were fan favorites all over the nation. One popular routine was called Shadow Ball. In this routine, the players pantomimmed an imaginary game of baseball with outlandish movements and stunts. Fans were thrilled when one player would pick up four baseballs and throw them at the same time to four different players. The Clowns toured the country until the early fifties. Their most famous alumnus was a young Mobile, Alabama outfielder by the name of Henry Aaron, who led the American National League with a .467 average - a miraculous feat considering he batted cross handed.

Dubliners had seen good Negro League players before. The Dublin Athletics, members of an independent Negro League, played on a field on East Mary Street near the Dudley Cemetery. They were a pretty fair team in their own right, but nothing could compare to that April day when two of the giants in the world of sports played on our field.